Story by Karry King Edited by: Ben Westhoff

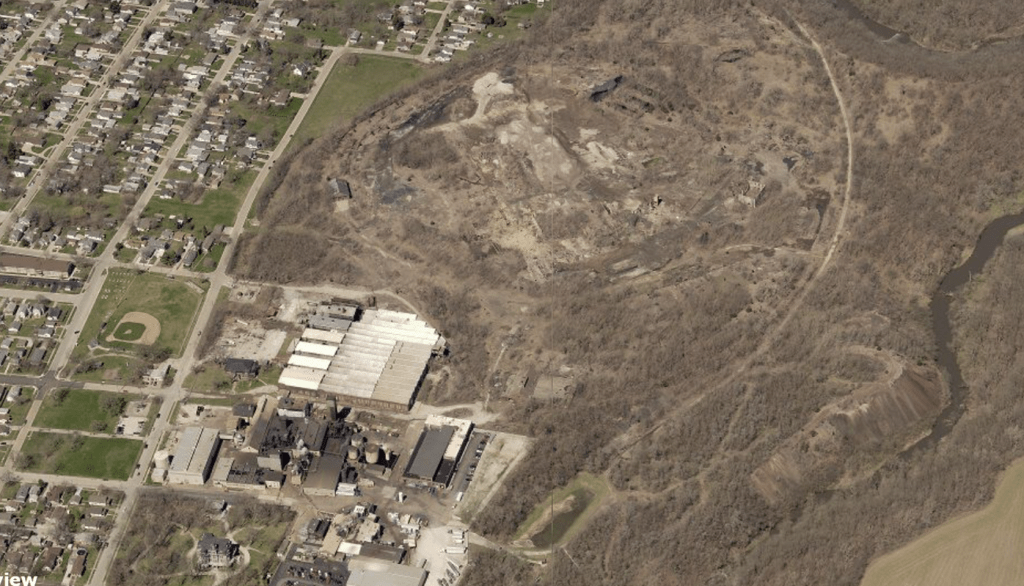

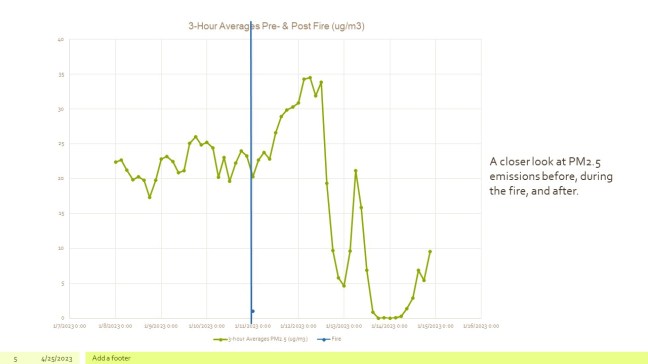

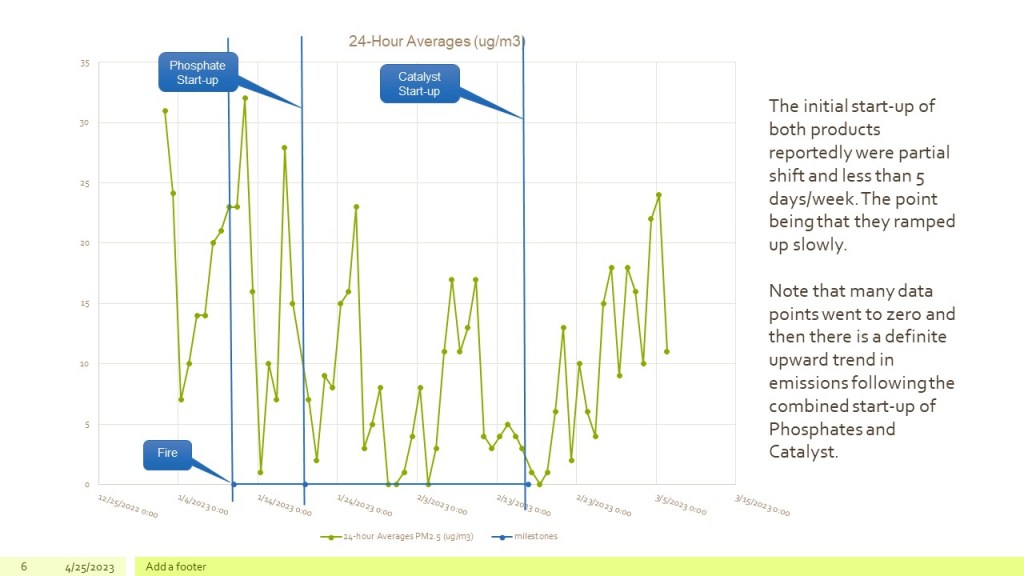

On the morning of January 11, a chemical manufacturing warehouse in La Salle, Illinois exploded.

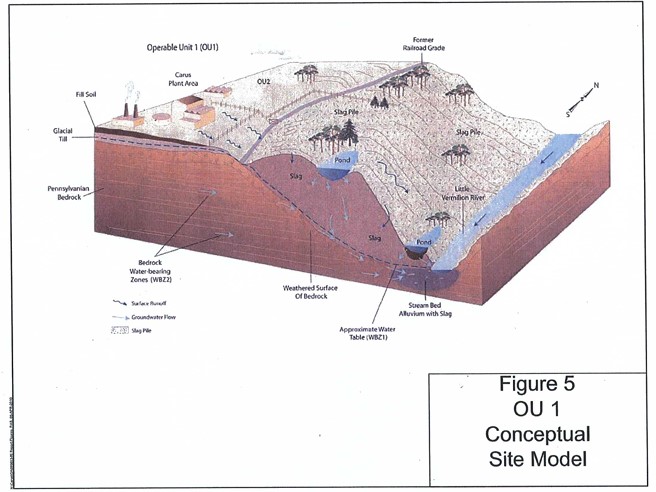

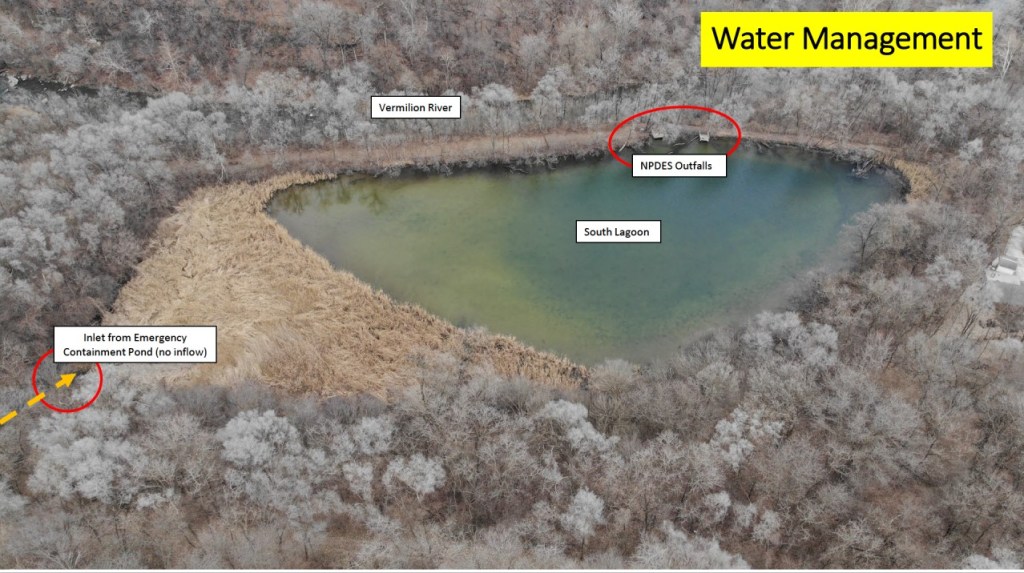

Orange flames ascended into a thick black cloud over the rural town, ninety miles southwest of Chicago. Over one million pounds of a chemical called potassium permanganate were released into the atmosphere, and the purple residue coated roofs, decks, cars, and yards. Streams of purple runoff flowed into the river via storm drains, according to reports.

La Salle’s fire chief ordered residents to stay in their homes and students to stay in their schools.

“I had purple stuff on my face and in my hair,” said Jamie Hicks, a LaSalle resident caught outside when it happened.

No alarms sounded. Townspeople could see smoke but didn’t know where it was coming from and wondered what was going on.

The company’s primary product, potassium permanganate, is best known as a chemical for treating municipal drinking water, and it is also used in mining, fracking, and refining crude oil. Illicit drug manufacturers also make cocaine with it, though there is no evidence that Carus’ chemicals are diverted for this purpose.

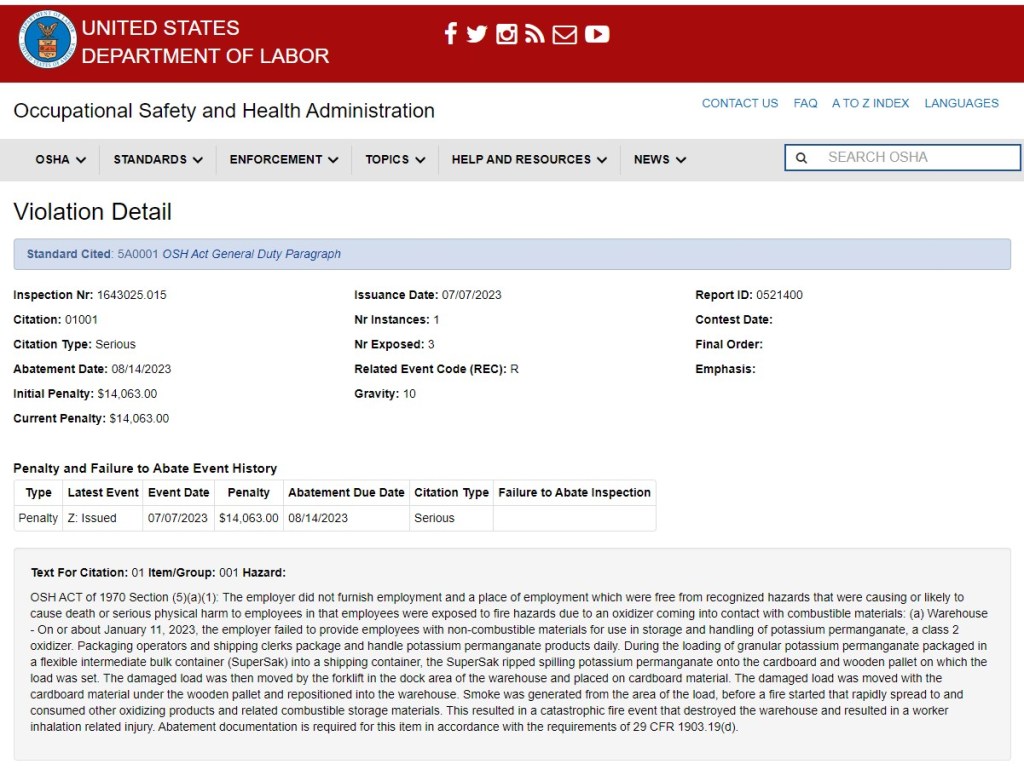

The explosion took place after a bag of potassium permanganate was accidentally torn open by a forklift while being loaded. Known to enhance combustion, the chemical ignited a piece of cardboard, and the fire quickly spread through the warehouse, causing several explosions. The U.S. Department of Labor fined Carus $14,000 for putting their workers’ lives in danger.

The company advised community members to use peroxide and vinegar to clean their homes, and offered free car washes. Sales representatives visited homes to assess the damage and assured residents that the chemicals were safe, say locals.

“This stuff etched into fiberglass on my boat,” said La Salle resident Don Gaddis. “[It] physically burnt right into the gel coat. It ate the paint off my vehicles…. But they’re telling us it’s safe.” (The company did not respond to our request for comment, but has made public claims about its chemicals’ safety, such as that fallout can be “safely rinsed away with water.”)

Metals including barium, manganese, copper, and lead have shown up in the soil, drinking water, and air filters inside residents’ homes.

Angry neighbors have held protests outside Carus’ headquarters. Convinced that the media isn’t telling the full story, they’ve also requested documents through the Freedom of Information Act from the EPA and state and local governments.

After five months of protests, Carus finally held a town hall meeting at the local high school on May 10. La Salle residents questioned Carus executives for two hours about the company’s history, practices, and EPA violations.

Some were upset that Carus stored chemicals near their homes in a building without a permit, neglecting to inform residents that it contained potassium permanganate, which is an explosive chemical.

“You could have killed all of us!” shouted Linda Battaglia at the meeting. “Sorry means nothing if there’s no action behind it.”

Erik Dyas, a certified hazardous materials trainer, said Carus should have enlisted a HazMat team to clean up the spill.

“Is the reason you didn’t call HazMat because it costs money?” asked Dyas. “If you’re putting your workers in danger, shame on you, not to mention you’re endangering everybody else.”

The uproar stands in contrast to the company’s previous peaceful coexistence with its neighbors in La Salle, where it has operated for over 100 years.

Its founding family members emigrated from Germany in 1856 to start a smelting company, choosing La Salle because of its resources — coal and zinc — and its proximity to the Illinois River and I & M Canal. They supplied zinc for Union armaments during the Civil War.

In 1915, grandson Edward Hegeler Carus began making potassium permanganate in a bathtub in the horse barn behind the family’s mansion after learning supplies had been cut off from Germany. He sold it to the U.S. government to use in explosives.

During the second World War, Carus Chemical supplied potassium permanganate to the U.S. government and was honored by the Navy for their contribution.

Edward’s son Blouke studied chemistry under Nobel Prize-winning chemist Hermann Staudinger at the University of Freiburg, Germany. After returning to the U.S. in 1951, Blouke and his brother Paul took over the management of Carus and revolutionized how potassium permanganate was made. By 1961, the company began marketing directly to U.S. cities. Today their chemical is used in over 50 percent of water consumed in the U.S.

Blouke’s daughter, Inga Carus, took over as Carus chairman in 2005, and Carus has continued dominating the industry, expanding across the globe. The company has opened branches in China and Spain, and remains in the midst a $20 million expansion of the La Salle plant, having resumed production and shipping within a week of the January explosion.

Yet many La Salle residents continue to be furious about the explosion and its fallout, saying it has negatively impacted their health, and that the company hasn’t taken full responsibility.

Lisa Dyas, who lives near the explosion site, says her 14-year-old son spent weeks in the hospital with severe pneumonia after the fire, and the fluid had barely left his lungs four months later.

“The chemical burned a hole in my chair. Don’t tell me it’s not harmful,” said Dyas.

April Stevenson, a La Salle single mom, said she had to get three teeth pulled because of infection from the chemicals and couldn’t breathe properly when Carus resumed production. She was forced to visit the emergency room twice, and her kids became sick with respiratory issues and infections. Others complain of headaches, racing heartbeats, nausea, and sick pets.

Stevenson said Carus’s insurance rejected her medical claims and offered her only $774 — for her ruined bicycles. Many residents want a full federal investigation of the company.

“Cancer and dementia are too common in our area,” said Marty Schneider, whose yard is full of dust from the factory’s smokestacks. “My dog gets sick as hell every time that stuff is in my yard. People are getting sick. It’s time [for Carus] to start being honest.”

The company said it has received over 100 insurance claims from affected residents; some used their personal carriers instead of going through Carus, and others refused to accept a settlement that required signing a form exempting Carus from future liability.

Reads the release: “The Releasor…will not make any statements, comments, or communications that … may be considered to be derogatory or detrimental to [Carus’] good name or business reputation.”

Karry King, a student at the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications, originally hails from the Illinois Valley. She has been covering chemical contamination and mining issues in the area since 2014. www.karryaking.wordpress.com